The persistent gender gap in corporate leadership has led several European countries to institute board-related policies such as gender quotas, starting with Norway in 2003. Recently, California became the first U.S. state to follow suit, with many more considering similar regulatory measures. Despite this, the World Economic Forum estimates that the gender gap in wages and leadership would not be bridged in the next two centuries at its current pace. It is hard to overstate the need to understand what company-level factors affect the gender pay gap. Moreover, given the public interest in reducing the gender imbalances at all levels, it is essential to understand if and how the regulatory interventions affect the top executives’ gender pay gap. Besides, to better design public policies in the future, it is vital to understand how effective the present regulations are.

In our recent paper, we examine the gender gap in executive pay, focusing on company-level factors and regulations. In regulations, we consider not only board gender quotas but also parental leave provisions. While the upper echelons of the corporate world are not the primary target of the parental leave provisions, it is an important public-policy instrument. Using over 15,000 executives of listed companies from 18 countries between 2002-2015, we follow a comparable cohort of executives appointed within our sample period throughout their tenure within a company. With this method, we show a structural gender gap in executive pay across the world. We document that female executives receive 34 percent less pay than male equivalents with similar education, experience, leadership roles, and other firm-level features. We also find a significant variation in the pay gap across industries; the executive gender pay gap is the highest in the banking and finance industry (57 percent), and lowest in the consumer goods industry (11 percent). Unsurprisingly, the gender pay gap is highest for the youngest female executives, who are more likely to be affected by proximate maternity breaks in their corporate careers.

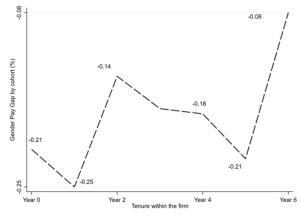

One of the novel findings from our study is that, unlike previously assumed, the gender gap is not a static feature within a company. We document that the gender pay gap diminishes with tenure. It means that once employers learn more about their female executives’ performance, they narrow the pay gap. It suggests that the gender pay gap is a dynamic learning process for employers rather than something that is purely a result of bias or prejudice. Notwithstanding the narrowing, the pay gap is never fully bridged throughout the female executives’ corporate tenure. Figure 1 shows this tenure-led narrowing of the pay gap trend, all things being equal.

Figure 1

The structural nature of the gender pay gap is the primary rationale for why public policies are potentially necessary. Board gender quotas are demand-side policies since they mandate companies to appoint female board members, creating additional demand for their services. In contrast, parental leave entitlements are supply-side policies that enable females to stay longer at work to have a better chance of being appointed as executives – and demanding higher wages – during their child-rearing years. Such policies could also help them return to work sooner. Prior research has shown that child-rearing demands are greatest on females. Therefore, it is essential to study how such policies affect highly-educated females in the workplace. Our results show that the pay disadvantage is lower for female executives in countries with board gender-quotas and parental leave provisions compared with countries that do not have these provisions.

A central question in designing public policies is, who should benefit? Often the answer is, the most disadvantaged group. In the corporate setting, younger females face a considerable disadvantage since they have to juggle home-life and corporate-life while attempting to climb the corporate ladder. Besides, as females, they face additional pressures that come with being “token” appointments. With experience, such disadvantages are likely to recede. It depends, however, on their staying power. Here public policies should help. We document that with quota-type public policies, established and senior females benefit more with not only significantly smaller pay gaps, but sometimes with a pay-premium. In contrast, young female executives benefit from the parental leave-type policies. Therefore, when facing gender quotas, companies react by appointing the senior female executives with more experience. On the other hand, supply-side policies such as parental leave entitlements reduce labor market frictions for younger women, enabling them to overcome their maternity pay discount.

The closure of the representation gap, an essential metric in itself, must be assessed in light of the overall aim of reducing gender barriers to corporate leadership. We hope that our results inform the debate on the nature of the executive gender pay gap and the design and effectiveness of public policies that aim to reduce institutional factors that create gender imbalance in the corporations. Gender quota policies’ allure is their rapid effect in the short-term. Nevertheless, in the longer-term, family policies, such as parental leave provisions that compensate the most disadvantaged group of young women directly, can be further explored as a complementary policy to address the gender gap.

This post comes to us from professors Swarnodeep Homroy and Shibashish Mukherjee at the University of Groningen. It is based on their recent article, “The Role of Employer Learning and Regulatory Interventions in Mitigating Executive Gender Pay Gap,” available here.

Sky Blog

Sky Blog