The widely accepted primary purpose of corporations is to maximize profit or value to shareholders, otherwise known as “shareholder primacy.” Shareholder primacy represents not only the prevalent objective of corporations but also a norm: A seminal case in corporate law, Dodge v. Ford Motor Co., set the cardinal principle that a corporation must serve the interests of shareholders rather than the interests of its employees, customers, or the community.

The court decision has set shareholder primacy as a legal obligation, not just a business objective, and created a distinction between corporate interests and the interests of other stakeholders such as employees, consumers, and the community at large. This separation has considerable social ramifications because corporate interests and those other interests are closely intertwined: A majority of the population are employees of corporations and meet their economic needs through the goods and services that corporations provide. Considering the extent of corporate influence today, the pursuit of shareholder interests over the interests of other stakeholders can cause considerable adverse effects, such as inattention to social and environmental harms.

Shareholder Primacy as the Law and as a Norm

The economic, social, and political powers of corporations today are incomparably stronger than those that existed at the time of the Dodge decision; thus, the economic and social impact of the decision upholding shareholder primacy would be significant, should the decision have legal effect. Academic views diverge: Some scholars, including Professor Lynn Stout, have argued that shareholder primacy is not the law and that the Dodge decision should not be considered relevant to current law, while others are more cautious about refuting its legal status. A critical examination of the scholarly arguments, relevant court cases, state statutes, and the statement of former Delaware Supreme Court Chief Justice Leo Strine indicate that shareholder primacy is the law, although its enforceability is questionable.

Shareholder primacy, regardless of its status as the law, has become a corporate norm: Shareholders’ innate human desires to see their shares of profit maximized – what we call “market forces” – would only be a natural driver of shareholder primacy. The prevalent result from this powerful combination – recognition of shareholder primacy as a norm and its promotion under market pressure – is corporations’ short-term profit-seeking. This has significant social ramifications, as the short-term profit seeking would justify behavior that might be contrary to the interests of society, such as cutting wages and customer support, but would improve profits for corporations in the short run. Short-term profit seeking may serve the interests of a group of powerful shareholders, such as institutional shareholders (e.g., hedge funds) seeking short-term profit, but undermine the interests of the other shareholders and the long-term prospects of the corporation.

Shareholder Primacy as a Flawed Principle for Corporate Governance

Shareholder primacy that purports to prioritize shareholders’ interests over the interests of other stakeholders is not tenable in practice because shareholder interests are not uniform, but varied, as illustrated below.

Suppose that Company A produces computer parts and decides to spend an additional $10 million a year to increase employee wages. The board claims that this decision, which seemingly benefits employees, will help the company recruit and retain superior employees, which will enhance productivity. Suppose that the company also announces the reduction of its product price by 10 percent, in response to its customer requests, resulting in the immediate loss of $10 million in revenue, and claims that the price reduction benefits its loyal customers but will also benefit the company by increasing its market share. The company presents the following projections.

|

Year |

Wage increase | Productivity increase | Price reduction

|

Market share increase | Total revenue change |

| Base year | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Year 1 | 10 | 5 | 10 | 5 | -10 |

| Year 2 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 0 |

| Year 3 | 10 | 15 | 10 | 15 | +10 |

| Year 4 | 10 | 15 | 10 | 15 | +10 |

| Year 5 | 10 | 15 | 10 | 15 | +10 |

Table 1: Revenue Projection by Year (unit: million U.S. dollars)

Dissimilar interests among shareholders create complexity. For shareholders with a short-term investment plan, the proposed spending benefits the employees and the customers but does not enhance shareholder wealth at all; i.e., for one-year investors (shareholders), they only see the loss of $10 million, for two-year investors, a $5 million loss (the average of $10 million loss in the first year and no loss in the second), for three-year investors, no gain or loss, for four-year investors, an average of a $2.5 million gain over the four-year period, and for five-year investors, an average of a $5 million gain over the five-year period.

Thus, the proposed action benefits shareholders who intend to stay with the company for four years or more but no less. So, whose shareholder interest must the company maximize or enhance? This is essentially a business decision that each corporation will have to make, not one that can be assessed and decided by a court. The court, unable to reconcile varied interests among shareholders, has no choice but to take the directors’ word at face value as long as they assert that they intend to enhance or maximize the interests of shareholders, whatever the projected period might be or however likely it is to be successful.

Shareholder Primacy as an Aggravating Factor for Economic Polarization

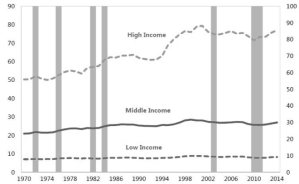

Corporate governance emphasizing shareholder primacy has also affected economic polarization. Giving shareholder value priority over all other corporate interests – and using stock options and other compensation packages to encourage CEOs and other high-level corporate officials to serve that priority – have led to an obsessive emphasis on short-term financial performance. Financial gains have not been reinvested to enhance productive activity but distributed to shareholders in dividend payments and share buy-backs, enriching a relatively small number of executives and shareholders while suppressing wages of the majority of workers, as illustrated in the following figure.

Figure 1: Average Scaled Household Income, 1970-2014 (thousand 2005 U.S. dollars) (Source: Ali Alichi, Kory Kantenga, & Juan Solé, Income Polarization in the United States, IMF Working Paper, WP/16/121, 2016)

The adverse effect of shareholder primacy on economic polarization is evident in the Gini coefficient comparison. The Gini coefficient represents the degree of income distribution – the higher the Gini coefficient, the greater the income gap between the richest and the poorest. The Gini coefficient is lower in countries where shareholder primacy is less prominent, such as France and Germany. The following table shows the comparison.

| Country | United States | France | Germany |

| Gini coefficient | 41.4 (2018) | 32.4 (2018) | 31.9 (2016) |

Table 2: Gini coefficient comparison

Shareholder primacy is perpetuating economic polarization. Eliminating such polarization and income inequality requires corporate governance that is driven not by shareholder primacy, but by stakeholder partnership that recognizes the contribution of the non-shareholding stakeholders, including employees, to corporate activities.

A Call for Legal Reform

Corporate interests and the broader economic interests of society are not mutually exclusive and can be reconciled by allowing corporate directors and managers to define corporate interests beyond shareholder primacy. There is no compelling public policy ground for limiting corporate interests to shareholders’ interests; if the controlling majority of shareholders support a board decision to promote broader economic interests, perhaps at the expense of maximizing immediate profits, there is no compelling reason for a court to find that such a decision violates the fiduciary duty owed to shareholders.

Corporations should not be compelled to resort to the argument of profit maximization to justify decisions that may appear contrary to shareholder primacy. Dissatisfied shareholders have recourse, including the ability to dispose of their stocks on the open market or to negotiate with the corporation to buy their stocks on mutually agreeable terms. The question of corporate interests must be left to each corporation, not to a court enforcing a legal mandate, regardless of the latter’s actual enforceability. The current situation is ambiguous: Many believe shareholder primacy is the law, some do not; some think it is an effective law, and others believe it is just aspirational. Legislatures need to clarify that shareholder primacy is not the law and that corporate management may freely consider the interests of stakeholders other than shareholders.

This post comes to us from Professor Yong-Shik Lee, director of the Law and Development Institute and visiting professor at Georgia State University College of Law. It is based on his recent article, “Reconciling Corporate Interests with Broader Social Interests – Pursuit of Corporate Interests Beyond Shareholder Primacy,” available here.

Sky Blog

Sky Blog